The Epigenetic Mechanisms of Gene Transcriptional Regulation and Its Dysregulation in Disease

Introduction

The processes of development and differentiation in eukaryotic systems are controlled by constantly changing cohorts of site-specific DNA-binding transcription factors, cofactors, chromatin regulators and varieties of cis-regulatory DNA elements or non-coding RNAs that direct cell-selective transcriptional programs1, 2, 3, 4, 5. A central paradigm in current biology from pioneering work to many subsequent studies, argues that transcription factors (trans-factors) occupy specific DNA sequences at control elements (cis-elements) and nucleate the transcription apparatus1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

The organization of eukaryotic genomes into complex nucleoprotein structures known as chromatin, elicits markedly restricted access of transcription factors to regulatory sites in a highly cell-specific manner1, 9, 10, 11. The effects of chromatin structure that impinge on gene transcriptional regulation can be divided into three general areas. First, a clear subset of histone modification marks are associated with cis-regulatory DNA elements; massively parallel short-read sequencing of chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA (ChIP–seq) has been used to study the genomic distributions of histone marks1, 9, 10, 12, 13. Second, inhibition of transcription factors access to the underlying DNA sequence by ordered chromatin structures has emerged as a common feature of gene regulation; chromatin accessibility could be measured by cleavage- or sonication-based high throughput sequencing methods14, 15, 16. Third, long-range interactions between distinct regulatory DNA elements occur on a wide scale; the chromosome conformation capture methodologies in various implementations open new windows for studying the role of nuclear architecture17, 18, 19, 20.

ChIP–seq Grade Antibody

|

ABclonal货号

|

产品名称

|

抗体来源

|

产品应用

|

应用物种

|

The recent insights into control of cellular gene expression programs and next-generation sequencing based characterization of chromatin structures have had an important impact on our understanding of epigenetic regulation of gene expression21. Misregulation of these gene expression programs can lead to a broad range of diseases and syndromes, including but not limited to cancer, neurological disorders and diabetes. Here, we summarize current understandings of transcriptional regulation in chromatin context and provide insights that how misregulation of transcription contributes to disease.

RNA Polymerase and Transcription Cycle

The eukaryotic genome is transcribed by three types of multisubunit RNA polymerase (Pol) enzymes, Pol I, II, and III. These polymerases synthesize different classes of cellular RNAs. Specifically, Pol I and III synthesize the 25S rRNA precursor and short untranslated RNAs such as transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and 5S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), respectively22, 23, 24. In eukaryotes, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is responsible for synthesizing all protein-coding RNAs and most non-coding RNAs, including long noncoding RNAs, small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) that contribute to control of gene expression through modulation of transcriptional or posttranscriptional processes25.

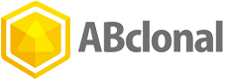

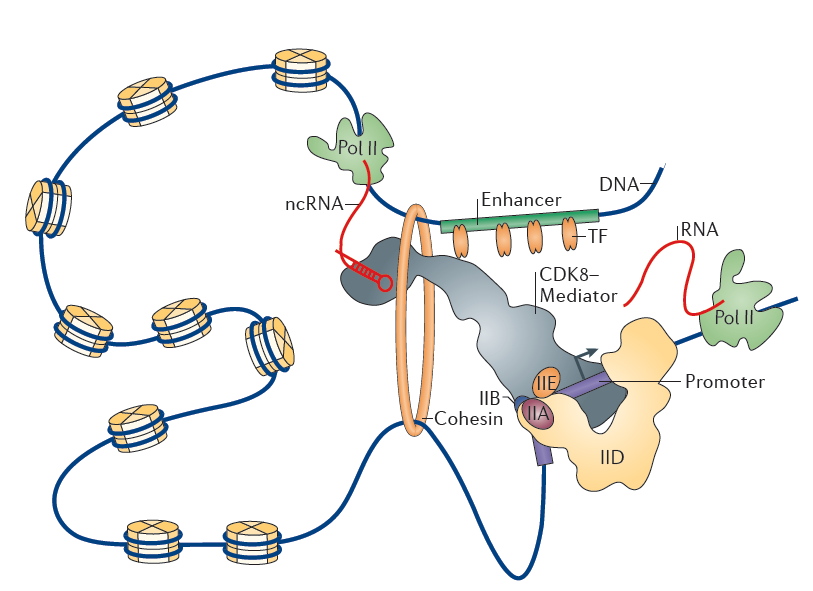

Figure 1. RNA polymerase II recruitment, initiation and gene entry, pausing and release. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 16, 167–177 (2015)

Classically, all stages of transcription cycle, including initiation, elongation and termination are subjected to RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) regulatory control

26, 27, 28. During initiation, the general transcription factors recognize core promoter elements (the minimal DNA sequences needed to specify nonregulated or basal transcription), recruit and orient the polymerase to form the preinitiation complex (PIC)

26. The DNA is then melted to expose the template strand and the first few nucleotides of RNA are synthesized. Subsequently, Pol II molecules transcribe a short distance, typically 20–60 base pairs (bp) in length, and then hold in a paused state until additional signals promote productive elongation

26, 28, 29. This promoter-proximal pausing predominantly occurs at genes in stimulus-responsive pathways and >70% of metazoan genes are subjected to this rate-limiting control26. The paused polymerases may terminate transcription with release of the small RNA species, or they may transition to active elongation through pause release and subsequent elongation. Termination occurs when Pol II ceases RNA synthesis and both Pol II and the nascent RNA are released from the DNA template. Along with transcription, histone modifications occur in characteristic patterns in different transcriptional phases. In particular, transcription initiation are typically linked with predominant enrichment of histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (

H3K4me3) and histone H3 lysine 79 dimethylation (

H3K79me2), while elongations are usually marked by histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation (

H3K36me3)

26, 30.

Transcription Factors and Gene Transcriptional Regulation

The processes of development and homeostasis in eukaryotic systems are directed by cell-specific transcriptional programs31, 32. This program includes RNA species from housekeeping genes that are active in most cells and cell-type-specific genes that are active predominantly in one or a limited number of cell types. It is now understood that the control of much of the active or silent gene expression program is dominated by a particular set of key transcription factors that act to establish and maintain specific cell states24, 25. Studies suggest that only a small number of the transcription factors are necessary to establish cell type specific gene expression programs32.

Transcription Factors Related Antibodies

|

ABclonal货号

|

产品名称

|

抗体来源

|

产品应用

|

应用物种

|

In molecular biology, a transcription factor is defined as a sequence specific DNA binding protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA8, 31. A defining feature of transcription factors is that they contain at least one DNA-binding domain (DBD), which attaches to a specific, conserved, and short DNA sequence element located at the proximal (promoter) or distant region (enhancer, insulator) to the genes that they regulate. Analysis from both in vitro and in vivo experiments indicates that transcription factors typically recognize 6-12 bp-long degenerate DNA sequences5, 32.

This intrinsic, fairly low sequence specificity suggests that more complex rules, other than the simple affinity of individual transcription factor for DNA, are involved in controlling both genomic occupancy and the functional outcome33. Typically, regulator regions contain clusters of different transcription factor binding sites. When the associated transcription factors are expressed in overlapping spatial domains and temporal windows in a particular cell, this combinatorial binding can result in discrete and precise patterns of transcriptional activity. Competition between transcription factors for the same binding site does not necessarily result in the quenching or interference of either factor's activity as might be expected, but can lead to an increased occupancy of each other8, 33, 34. The rapidly alternating occupancy of each transcription factor is proposed to counteract nucleosome repositioning, and therefore assist a net increase for other transcription factor binding. Alternatively, transcription factor binding can also trigger local bending of DNA, which facilitates the binding of a neighboring transcription factor to regulatory element. These mechanisms convert low-affinity DNA interactions into robust binding events and concerted action for transcription factors to impact on gene expression collaboratively. On the other side, transcription factor occupancy is also influenced by nucleosome positioning, in which histones and transcription factors compete for access to the DNA. In general, transcription factor binding profiles are highly correlated with nucleosome-depleted regions (NDRs) in eukaryotic cells, suggesting that nucleosome positioning determines which site a transcription factor can occupy35. Chromatin remodelling–regulated nucleosome mobilizing or histone chaperone –directed histone eviction is a prerequisite for the occupancy of TF in some cases. For example, in mammals, loading of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) at a number of sites demands chromatin remodelling by the SWI/SNF complex36, and hormone-responsive elements (HREs) require the chromatin-remodelling complexes BAF and PCAF to facilitate nuclear receptor binding37.

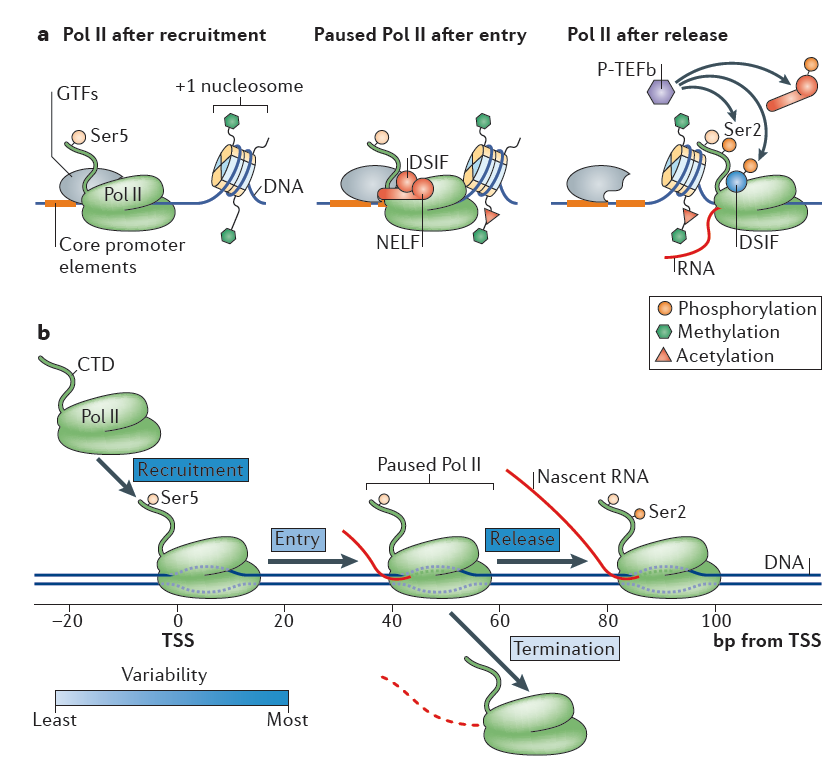

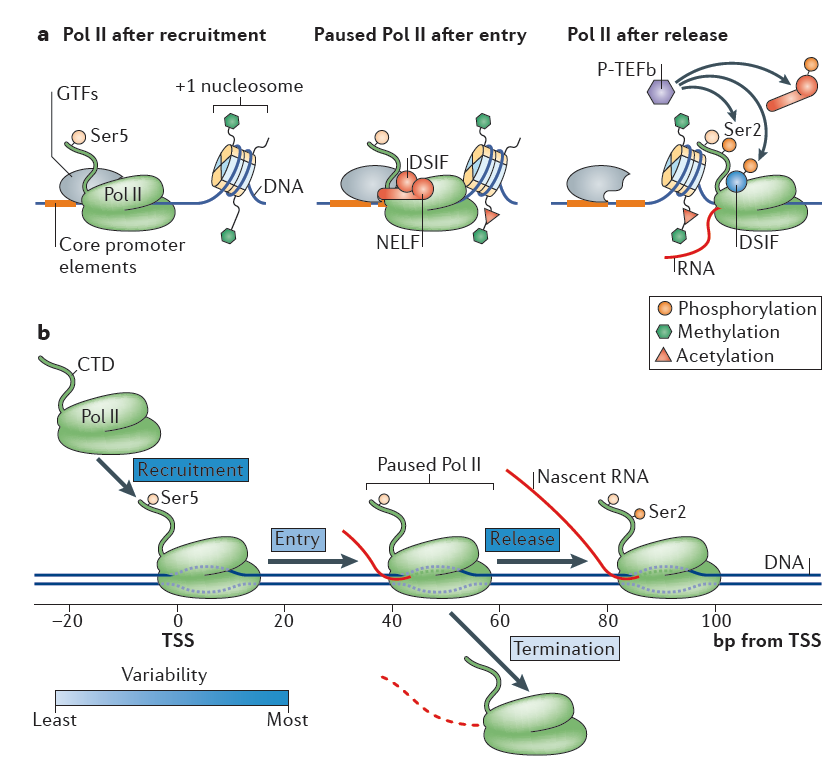

Generally, gene transcriptional regulation occurs at two interconnected dimensions: the first involves transcription factors recruitment, and the second involves transcription associated chromatin reorganization. Transcription factors work with other proteins (co-factor) in a complex, by promoting (as an activator), or blocking (as a repressor) the recruitment of RNA polymerase to specific genes24, 33, 34. An array of histone-modifying enzymes that acetylate/deacetylate, methylate/demethylate, or ubiqutinate/deubiqutinate and otherwise chemically modify nucleosomes in a stereotypical fashion across the span of each gene is recruited by transcription factors, producing a highly dynamic process of chromatin modification4, 7. Promoters of active genes display a high level of tri-methylation on H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3), while repressed genes are embedded in chromatin with modifications that are characteristic of specific repression mechanisms4, 32. One type of repressed chromatin, which marked by tri-methylation on H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) generated by the Polycomb complex, is found at genes that are silent but poised for activation at some later stage of development and differentiation in embryonic stem cells2, 5. Another type of repressed chromatin demarcated by tri-methylation on H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and DNA methylation.is found in regions of the genome that are fully silenced, such as retrotransposons and other repetitive elements32. Until now, many types of histone modification-binding modules (for example, bromodomains, chromodomains, tudor domains, malignant brain tumor (MBT) domains, and plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers) for acetylation or methylation have been identified31, 38. Protein complexes encompassing these modules recognize corresponding modifications and actively or repressively contribute to gene transcriptional control.

Figure 2. Transcription coupled chromatin modification and remodeling. Front. Mol. Neurosci., 12 January 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2011.00060

Cis-Regulatory DNA Elements

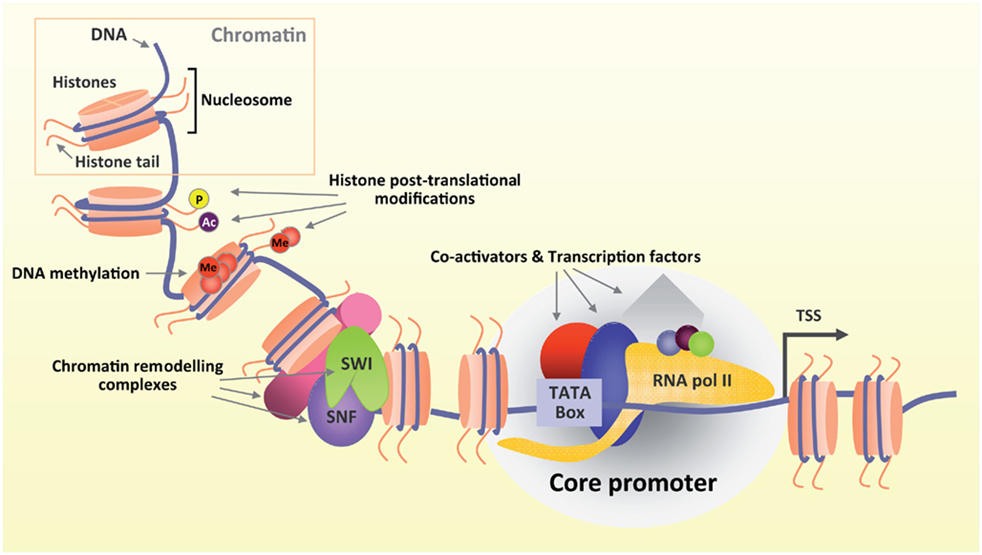

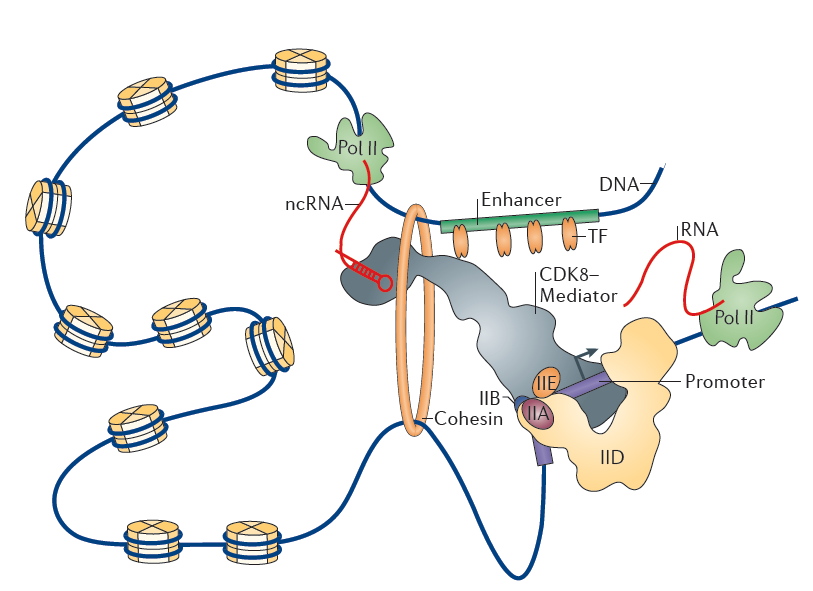

As stated above, transcription of a gene in eukaryotes requires precise coordination of transcription factors through the recognition of various types of regulatory DNA sequences. The promoter and the enhancer represent the most relevant DNA regulatory regions that allow spatiotemporally accurate expression of eukaryotic genes. The promoter generally refers to a DNA region responsible for transcription initiation of a gene. The core promoter is a minimal stretch of DNA sequences surrounding the transcription start site that acts to assembly of basal transcription machinery, including RNAPII. Transcription factors that bind their cognate DNA sequences, usually 100–200 bp upstream of the core promoter, can increase the rate of transcription by facilitating the recruitment or assembly of the basal transcription machinery onto the core promoter or by tethering specific distal regulatory DNA sequences to the core promoter21. These distal sequences, known as enhancers, increase the rate of transcription independent of their position and orientation with respect to target genes39. Multiple transcription factors typically bind in a cooperative fashion to individual enhancers and regulate transcription through physical contacts that involve looping of the DNA between enhancers and the corresponding promoters40, 41. The cooperative interactions among Mediator complex, transcription factors, cohesin and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) regulates the formation of enhancer-promoter loops42, 43, 44.

Enhancers can be identified by genome wide profiling the locations of key transcriptional regulators and by examination of chromatin accessibility with DNase-seq, FAIREseq, and ATAC-seq for those without any prior knowledge of transcription factor binding motifs or transcription factor binding39. Massive sequencing analysis indicates that enhancers of active genes generally display a high level of mono- or di-methylation on H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1,H3K4me2) and acetylation of H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac) mark, but are nearly devoid of H3K4me333, 39, 40. These features can also be used to identify putative enhancers. A set of recent studies revealed that a few hundred enhancers in a given cell are clustered in large domains where a single enhancer communicate with each other physically and functionally, and are enriched with high level of Mediator complex binding or H3K27ac marks45, 46. These types of enhancers, defined as super-enhancers, are often located at cell-type-specific genes, and provide a platform where various signaling pathways converge to robustly regulate genes that control cell identity during development and tumorigenesis42, 46, 47, 48. Interestingly, certain percentage of enhancers also exhibit a significant level of histone H3K27 acetylase CBP and RNAPII binding and produce RNA transcripts49. These enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) are dynamically regulated, and are transcribed from the center of enhancers50. Several recent studies have suggested that the eRNA transcript itself might have an activating role in target gene expression through regulating enhancer-promoter looping, chromatin remodeling, and early transcription elongation in various cell types39.

The roles of promoters and enhancers in transcription have been thought to be distinct; however, these two regulatory elements are highly interrelated and show noticeable similarities in structure and function. A striking feature of eRNA transcription is bi-directionality, which is applicable to many enhancers10, 42. Similarly, the majority of mammalian promoters also drive divergent transcription, resulting in the production of short antisense ncRNAs (known as anti-sense RNAs)11, 14. Divergent transcription at promoters and enhancers is mediated by independent RNAPII transcription complexes assembled at each transcription starting sites (TSSs), which is intrinsically configured by underlying core elements as well as transcription factor binding motifs enriched near both sense and anti-sense TSSs33. In contrast to the promoter-driven mRNAs, eRNAs and upstream anti-sense RNAs are shorter in length (a few hundred base pairs up to a few kilobases) without splicing or polyadenylation and are large less stable41. However, as far as chromatin accessibility and transcription initiation are concerned, there appears to be very little difference between the promoter and the enhancer.

Figure 3. Chromatin loop between enhancer and promoter. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 16, 155–166 (2015)

Misregulated Gene Expression in Disease

Many diseases and syndromes are associated with mutations or dysregulation in transcription factors, transcription apparatus and chromatin regulators as well as in regulatory regions, aberrant of which are largely linked to misregulation of gene expression. The oncogenic transcription factor TAL1 that forms an interconnected autoregulatory loop with several key transcription factor partners, is overexpressed in approximately half of the cases of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and drives the oncogenic program in T-ALL51. Alterations of some transcription factors that control RNA polymerase II pause release and elongation can produce aggressive tumor cells (c-Myc) or some forms of autoimmunity (autoimmune regulator, AIRE)39. Mutations in the cohesin loading protein NIPBL that contributes to DNA looping can cause a broad spectrum of developmental diseases including growth and mental retardation, limb deformities, and craniofacial anomalies52, whereas mutations in MED23 or MED12, components of the Mediator coactivator complex, alter the interaction between enhancer-bound transcription factors and Mediator and lead to transcriptional dysregulation thus defects in brain development and neuron plasticity53, 54. Alterations in several nucleosome remodeling proteins, including ARID1A, SMARCA4 (BRG1), and SMARCB1 (INI1), are associated with multiple types of cancer55, while various mutations in the Polycomb components EZH2 and SUZ12 and in the DNA methylation apparatus occur in multiple cancers, suggesting that, in these instances39, 56, the defects in mobilizing nucleosomes or the loss of proper gene silencing, respectively, contributes to tumorigenesis.

Corroborating the importance of regulatory regions in gene transcriptional regulation, several lines of evidence suggest that much of genetic variation contributes to disease through misregulation of gene expression: 1) The frequency of SNPs that are linked to defects in glucose homeostasis and diabetes is greatly enriched in the binding sites for transcription factors including HNF1α, HNF1β, HNF4a, PDX1, and NEUROD1, some of which contribute to the interconnected autoregulatory circuitry of pancreatic cells57. 2) Many recent studies have identified links between disease-associated variants in regulatory DNA and a broad spectrum of human diseases, including cancer, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and coronary artery disease39, 58; 3) Disease-associated genetic variants in regulatory regions , in particular enhancers, are most often found in regions that are utilized in a cell-type-specific manner59, 60.

Conclusion

Genome-wide studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the chromatin structure and genomic architecture that underlies gene expression. Integrative analyses of the transcriptome, transcription factor or binding profiles, histone modification distributions, chromatin accessibility and chromosome conformation reveal complex organization of individual transcription units that integrate information from regulatory sequences and the key transcription factors, cofactors, chromatin regulators, and ncRNAs (e.g. eRNA and anti-sense RNA) nucleated at regulatory sites. Further studies of chromatin architecture and enhancer–promoter gene loops should yield fundamental insights into the mechanism of gene transcriptional regulation and benefit the treatment of gene misregulation associated disease.

Author Information

Nan Song, Ph. D.,

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Tianjin Medical University

References

-

1、Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 144, 16-26 (2011).

-

2、Stuwe E, Toth KF, Aravin AA. Small but sturdy: small RNAs in cellular memory and epigenetics. Genes Dev 28, 423-431 (2014).

-

3、Josefowicz SZ, Shimada M, Armache A, Li CH, Miller RM, Lin S, Yang A, Dill BD, Molina H, Park HS, Garcia BA, Taunton J, Roeder RG, Allis CD. Chromatin Kinases Act on Transcription Factors and Histone Tails in Regulation of Inducible Transcription. Mol Cell 64, 347-361 (2016).

-

4、Trouche D, Khochbin S, Dimitrov S. Chromatin and epigenetics: dynamic organization meets regulated function. Mol Cell 12, 281-286 (2003).

-

5、Robison AJ, Nestler EJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 623-637 (2011).

-

6、van der Knaap JA, Verrijzer CP. Undercover: gene control by metabolites and metabolic enzymes. Genes Dev 30, 2345-2369 (2016).

-

7、Lawrence M, Daujat S, Schneider R. Lateral Thinking: How Histone Modifications Regulate Gene Expression. Trends Genet 32, 42-56 (2016).

-

8、Shibata M, Gulden FO, Sestan N. From trans to cis: transcriptional regulatory networks in neocortical development. Trends Genet 31, 77-87 (2015).

-

9、Huang H, Sabari BR, Garcia BA, Allis CD, Zhao Y. SnapShot: histone modifications. Cell 159, 458-458 e451 (2014).

-

10、Papp B, Plath K. Epigenetics of reprogramming to induced pluripotency. Cell 152, 1324-1343 (2013).

-

11、Lu C, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab 16, 9-17 (2012).

-

12、Sun W, Poschmann J, Cruz-Herrera Del Rosario R, Parikshak NN, Hajan HS, Kumar V, Ramasamy R, Belgard TG, Elanggovan B, Wong CC, Mill J, Geschwind DH, Prabhakar S. Histone Acetylome-wide Association Study of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cell 167, 1385-1397 e1311 (2016).

-

13、Preissl S, Schwaderer M, Raulf A, Hesse M, Gruning BA, Kobele C, Backofen R, Fleischmann BK, Hein L, Gilsbach R. Deciphering the Epigenetic Code of Cardiac Myocyte Transcription. Circ Res 117, 413-423 (2015).

-

14、Wu J, Huang B, Chen H, Yin Q, Liu Y, Xiang Y, Zhang B, Liu B, Wang Q, Xia W, Li W, Li Y, Ma J, Peng X, Zheng H, Ming J, Zhang W, Zhang J, Tian G, Xu F, Chang Z, Na J, Yang X, Xie W. The landscape of accessible chromatin in mammalian preimplantation embryos. Nature 534, 652-657 (2016).

-

15、Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 10, 1213-1218 (2013).

-

16、Rendeiro AF, Schmidl C, Strefford JC, Walewska R, Davis Z, Farlik M, Oscier D, Bock C. Chromatin accessibility maps of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia identify subtype-specific epigenome signatures and transcription regulatory networks. Nat Commun 7, 11938 (2016).

-

17、Spurrell CH, Dickel DE, Visel A. The Ties That Bind: Mapping the Dynamic Enhancer-Promoter Interactome. Cell 167, 1163-1166 (2016).

-

18、Li X, Luo OJ, Wang P, Zheng M, Wang D, Piecuch E, Zhu JJ, Tian SZ, Tang Z, Li G, Ruan Y. Long-read ChIA-PET for base-pair-resolution mapping of haplotype-specific chromatin interactions. Nat Protoc 12, 899-915 (2017).

-

19、Ramani V, Cusanovich DA, Hause RJ, Ma W, Qiu R, Deng X, Blau CA, Disteche CM, Noble WS, Shendure J, Duan Z. Mapping 3D genome architecture through in situ DNase Hi-C. Nat Protoc 11, 2104-2121 (2016).

-

20、Stevens TJ, Lando D, Basu S, Atkinson LP, Cao Y, Lee SF, Leeb M, Wohlfahrt KJ, Boucher W, O'Shaughnessy-Kirwan A, Cramard J, Faure AJ, Ralser M, Blanco E, Morey L, Sanso M, Palayret MG, Lehner B, Di Croce L, Wutz A, Hendrich B, Klenerman D, Laue ED. 3D structures of individual mammalian genomes studied by single-cell Hi-C. Nature 544, 59-64 (2017).

-

21、Schmitt AD, Hu M, Ren B. Genome-wide mapping and analysis of chromosome architecture. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17, 743-755 (2016).

-

22、Geiduschek EP, Kassavetis GA. Comparing transcriptional initiation by RNA polymerases I and III. Curr Opin Cell Biol 7, 344-351 (1995).

-

23、Lisica A, Engel C, Jahnel M, Roldan E, Galburt EA, Cramer P, Grill SW. Mechanisms of backtrack recovery by RNA polymerases I and II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 2946-2951 (2016).

-

24、Zhang Y, Najmi SM, Schneider DA. Transcription factors that influence RNA polymerases I and II: To what extent is mechanism of action conserved? Biochim Biophys Acta 1860, 246-255 (2017).

-

25、Struhl K. Transcriptional noise and the fidelity of initiation by RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14, 103-105 (2007).

-

26、Adelman K, Lis JT. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet 13, 720-731 (2012).

-

27、Bunch H, Zheng X, Burkholder A, Dillon ST, Motola S, Birrane G, Ebmeier CC, Levine S, Fargo D, Hu G, Taatjes DJ, Calderwood SK. TRIM28 regulates RNA polymerase II promoter-proximal pausing and pause release. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 876-883 (2014).

-

28、Core LJ, Lis JT. Transcription regulation through promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. Science 319, 1791-1792 (2008).

-

29、Krumm A, Hickey LB, Groudine M. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II defines a general rate-limiting step after transcription initiation. Genes Dev 9, 559-572 (1995).

-

30、Day DS, Zhang B, Stevens SM, Ferrari F, Larschan EN, Park PJ, Pu WT. Comprehensive analysis of promoter-proximal RNA polymerase II pausing across mammalian cell types. Genome Biol 17, 120 (2016).

-

31、Voss TC, Hager GL. Dynamic regulation of transcriptional states by chromatin and transcription factors. Nat Rev Genet 15, 69-81 (2014).

-

32、Kim TK, Shiekhattar R. Architectural and Functional Commonalities between Enhancers and Promoters. Cell 162, 948-959 (2015).

-

33、Spitz F, Furlong EEM. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nature Reviews Genetics 13, 613-626 (2012).

-

34、Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet 17, 520-527 (2001).

-

35、Lupien M, Eeckhoute J, Meyer CA, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Li W, Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brown M. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell 132, 958-970 (2008).

-

36、John S, Sabo PJ, Thurman RE, Sung MH, Biddie SC, Johnson TA, Hager GL, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat Genet 43, 264-268 (2011).

-

37、Vicent GP, Zaurin R, Nacht AS, Li A, Font-Mateu J, Le Dily F, Vermeulen M, Mann M, Beato M. Two chromatin remodeling activities cooperate during activation of hormone responsive promoters. PLoS Genet 5, e1000567 (2009).

-

38、Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res 21, 381-395 (2011).

-

39、Lee TI, Young RA. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell 152, 1237-1251 (2013).

-

40、Whyte WA, Bilodeau S, Orlando DA, Hoke HA, Frampton GM, Foster CT, Cowley SM, Young RA. Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 482, 221-225 (2012).

-

41、Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, Zhan Y, Orlando DA, van Berkum NL, Ebmeier CC, Goossens J, Rahl PB, Levine SS, Taatjes DJ, Dekker J, Young RA. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature 467, 430-435 (2010).

-

42、Suzuki HI, Young RA, Sharp PA. Super-Enhancer-Mediated RNA Processing Revealed by Integrative MicroRNA Network Analysis. Cell 168, 1000-1014 e1015 (2017).

-

43、Shu S, Lin CY, He HH, Witwicki RM, Tabassum DP, Roberts JM, Janiszewska M, Huh SJ, Liang Y, Ryan J, Doherty E, Mohammed H, Guo H, Stover DG, Ekram MB, Peluffo G, Brown J, D'Santos C, Krop IE, Dillon D, McKeown M, Ott C, Qi J, Ni M, Rao PK, Duarte M, Wu SY, Chiang CM, Anders L, Young RA, Winer EP, Letai A, Barry WT, Carroll JS, Long HW, Brown M, Liu XS, Meyer CA, Bradner JE, Polyak K. Response and resistance to BET bromodomain inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Nature 529, 413-417 (2016).

-

44、Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, Young RA. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307-319 (2013).

-

45、Chapuy B, McKeown MR, Lin CY, Monti S, Roemer MG, Qi J, Rahl PB, Sun HH, Yeda KT, Doench JG, Reichert E, Kung AL, Rodig SJ, Young RA, Shipp MA, Bradner JE. Discovery and characterization of super-enhancer-associated dependencies in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell 24, 777-790 (2013).

-

46、Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Lau A, Saint-Andre V, Sigova AA, Hoke HA, Young RA. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934-947 (2013).

-

47、Buffry AD, Mendes CC, McGregor AP. The Functionality and Evolution of Eukaryotic Transcriptional Enhancers. Adv Genet 96, 143-206 (2016).

-

48、Chipumuro E, Marco E, Christensen CL, Kwiatkowski N, Zhang T, Hatheway CM, Abraham BJ, Sharma B, Yeung C, Altabef A, Perez-Atayde A, Wong KK, Yuan GC, Gray NS, Young RA, George RE. CDK7 inhibition suppresses super-enhancer-linked oncogenic transcription in MYCN-driven cancer. Cell 159, 1126-1139 (2014).

-

49、Wang D, Garcia-Bassets I, Benner C, Li W, Su X, Zhou Y, Qiu J, Liu W, Kaikkonen MU, Ohgi KA, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD. Reprogramming transcription by distinct classes of enhancers functionally defined by eRNA. Nature 474, 390-394 (2011).

-

50、Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E, Kuhl D, Bito H, Worley PF, Kreiman G, Greenberg ME. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature 465, 182-187 (2010).

-

51、Sanda T, Lawton LN, Barrasa MI, Fan ZP, Kohlhammer H, Gutierrez A, Ma W, Tatarek J, Ahn Y, Kelliher MA, Jamieson CH, Staudt LM, Young RA, Look AT. Core transcriptional regulatory circuit controlled by the TAL1 complex in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 22, 209-221 (2012).

-

52、Kawauchi S, Calof AL, Santos R, Lopez-Burks ME, Young CM, Hoang MP, Chua A, Lao T, Lechner MS, Daniel JA, Nussenzweig A, Kitzes L, Yokomori K, Hallgrimsson B, Lander AD. Multiple organ system defects and transcriptional dysregulation in the Nipbl(+/-) mouse, a model of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. PLoS Genet 5, e1000650 (2009).

-

53、Hashimoto S, Boissel S, Zarhrate M, Rio M, Munnich A, Egly JM, Colleaux L. MED23 mutation links intellectual disability to dysregulation of immediate early gene expression. Science 333, 1161-1163 (2011).

-

54、Makinen N, Mehine M, Tolvanen J, Kaasinen E, Li Y, Lehtonen HJ, Gentile M, Yan J, Enge M, Taipale M, Aavikko M, Katainen R, Virolainen E, Bohling T, Koski TA, Launonen V, Sjoberg J, Taipale J, Vahteristo P, Aaltonen LA. MED12, the mediator complex subunit 12 gene, is mutated at high frequency in uterine leiomyomas. Science 334, 252-255 (2011).

-

55、Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 150, 12-27 (2012).

-

56、Cedar H, Bergman Y. Programming of DNA methylation patterns. Annu Rev Biochem 81, 97-117 (2012).

-

57、Maurano MT, Humbert R, Rynes E, Thurman RE, Haugen E, Wang H, Reynolds AP, Sandstrom R, Qu H, Brody J, Shafer A, Neri F, Lee K, Kutyavin T, Stehling-Sun S, Johnson AK, Canfield TK, Giste E, Diegel M, Bates D, Hansen RS, Neph S, Sabo PJ, Heimfeld S, Raubitschek A, Ziegler S, Cotsapas C, Sotoodehnia N, Glass I, Sunyaev SR, Kaul R, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science 337, 1190-1195 (2012).

-

58、Demichelis F, Setlur SR, Banerjee S, Chakravarty D, Chen JY, Chen CX, Huang J, Beltran H, Oldridge DA, Kitabayashi N, Stenzel B, Schaefer G, Horninger W, Bektic J, Chinnaiyan AM, Goldenberg S, Siddiqui J, Regan MM, Kearney M, Soong TD, Rickman DS, Elemento O, Wei JT, Scherr DS, Sanda MA, Bartsch G, Lee C, Klocker H, Rubin MA. Identification of functionally active, low frequency copy number variants at 15q21.3 and 12q21.31 associated with prostate cancer risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 6686-6691 (2012).

-

59、Li G, Ruan X, Auerbach RK, Sandhu KS, Zheng M, Wang P, Poh HM, Goh Y, Lim J, Zhang J, Sim HS, Peh SQ, Mulawadi FH, Ong CT, Orlov YL, Hong S, Zhang Z, Landt S, Raha D, Euskirchen G, Wei CL, Ge W, Wang H, Davis C, Fisher-Aylor KI, Mortazavi A, Gerstein M, Gingeras T, Wold B, Sun Y, Fullwood MJ, Cheung E, Liu E, Sung WK, Snyder M, Ruan Y. Extensive promoter-centered chromatin interactions provide a topological basis for transcription regulation. Cell 148, 84-98 (2012).

-

60、Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, Ku M, Durham T, Kellis M, Bernstein BE. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 473, 43-49 (2011).